An Ode to Olives

Way back in time, on a visit to Rome, Luanne and I wandered through the ancient ruins of the Roman Forum. It was late summer. The grass was flattened and yellow, tourists everywhere. Only three plants were to be seen… an old grape vine, a bedraggled fig tree, and an olive tree with just a couple of olives hanging from it.

Way back in time, on a visit to Rome, Luanne and I wandered through the ancient ruins of the Roman Forum. It was late summer. The grass was flattened and yellow, tourists everywhere. Only three plants were to be seen… an old grape vine, a bedraggled fig tree, and an olive tree with just a couple of olives hanging from it.

It was 1998, and Luanne and I had been considering our options in starting a new venture in Italian varietal wine. Then it hit us! Italian varietal wine, olive oil and figs. Three unmistakably Italian products, all from one tree (symbolically, the farm), and all well suited to Mudgee’s central west tableland.

In the years since then, di Lusso Estate’s wine and fig offerings have forged ahead of olives in dollars and effort and di Lusso olives don’t have much of a profile.

However, in the ‘bigger picture’ of world history, olives are arguably ahead of both wine and figs. This much loved tree, feature of countless biblical and historical stories has been around as possibly the world’s oldest commercially grown plant for 5,000 years at least.

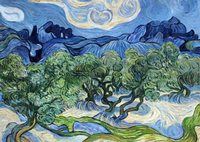

Olive trees and olive groves have been a favourite subject for some of the greatest artists. From the Renaissance painters of the 15th century to the contemporary painters, olives are depicted in various styles and forms, each a tribute to the magic of this tree.

Olive trees and olive groves have been a favourite subject for some of the greatest artists. From the Renaissance painters of the 15th century to the contemporary painters, olives are depicted in various styles and forms, each a tribute to the magic of this tree.

I remember, at one time during the early days of di Lusso, I collected fifteen prints of van Gogh’s olive paintings and hung them around the winery. The obsession faded, and the prints can’t be found. I’m sorry about that, but I can at least quote one of van Gogh’s many thoughts on the subject.

“The effect of daylight and the sky means there are endless subjects to be found in olive trees. For myself I look for the contrasting effects in the foliage, which changes with the tones of the sky. At times, when the tree bares its pale blossoms and big blue flies, emerald fruit beetles and cicadas in great numbers fly about, everything is immersed in pure blue. Then, as the bronzer foliage takes on more mature tones, the sky is radiant and streaked with green and orange, and then again, further into autumn, the leaves take on violet tones something of the colour of a ripe fig, and this violet effect manifests itself most fully with the contrast of the large, whitening sun within its pale halo of light lemon.”

Van Gogh is right, of course. The colours of an olive tree are extraordinary… at times khaki, at others almost emerald. Sometimes the tree is washed in grey.

And the fruit is similarly deceptive. Just when you think there’s nothing there, you can suddenly see a myriad of what look like peppercorns, well-camouflaged. These are the emerging olive flowers.

A week or so later – around mid-November – the canopy explodes in a white cloud of beautiful flowers. This is the time that we pray for windless days, to allow the fruit to set.

But in 2019, the same winds that drove the bush fire smoke towards Mudgee blew through our olive grove as well. And that was that! Flowers shriveled and burnt - practically no crop in 2020.

That’s farming!

But there are commercial risks on top of climatic ones. Most stem from mislabeling. Commercially, there are three different grades of olive oil made and marketed, around the world, from the high-quality extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) to medium-quality ordinary virgin olive oil, to low-quality olive-pomace oil (OPO).

EVOO is obtained by direct pressing or centrifugation of the olives. Its acidity can be no greater than 1 percent; if it is processed when the temperature of the olives is below 30°C - it is called cold-pressed. (Cold-pressing olives adds density of flavour and texture.)

Olive oils with between 1 and 3 percent acidity are known as "ordinary virgin" oils, but anything with greater than 3 percent acid and refined is " by accepted chemical solvents”, can also be fairly marketed as "ordinary." The dry or pulpy residue of the olive pressing process is called pomace, from which a liquid (such as juice or oil) has been pressed or extracted.

In Australia, all the supermarket chains seem to turn a blind eye to the mislabeling of ordinary virgin olive oil – in terms of country of origin (for example it is said that many Spanish olive oils are marketed as Italian) and many oils with more than 3% of acid are marketed as EVOO. But perhaps the most common adulterants in mis-labelled virgin olive oils are refined olive oil containing synthetic oil-glycerol products, seed oils (such as sunflower, soy, maize, and grapeseed), and nut oils (such as peanut or hazelnut).

So, if you’re interested in tasting the best, refer to a source such as Choice to decide which supermarket oils are ‘honest’ and put the list in your pocket when going shopping!

Rob