Our Blog

An Ode to Olives

Way back in time, on a visit to Rome, Luanne and I wandered through the ancient ruins of the Roman Forum. It was late summer. The grass was flattened and yellow, tourists everywhere. Only three plants were to be seen… an old grape vine, a bedraggled fig tree, and an olive tree with just a couple of olives hanging from it.

Way back in time, on a visit to Rome, Luanne and I wandered through the ancient ruins of the Roman Forum. It was late summer. The grass was flattened and yellow, tourists everywhere. Only three plants were to be seen… an old grape vine, a bedraggled fig tree, and an olive tree with just a couple of olives hanging from it.

It was 1998, and Luanne and I had been considering our options in starting a new venture in Italian varietal wine. Then it hit us! Italian varietal wine, olive oil and figs. Three unmistakably Italian products, all from one tree (symbolically, the farm), and all well suited to Mudgee’s central west tableland.

In the years since then, di Lusso Estate’s wine and fig offerings have forged ahead of olives in dollars and effort and di Lusso olives don’t have much of a profile.

However, in the ‘bigger picture’ of world history, olives are arguably ahead of both wine and figs. This much loved tree, feature of countless biblical and historical stories has been around as possibly the world’s oldest commercially grown plant for 5,000 years at least.

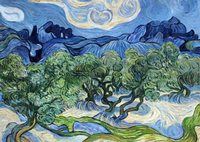

Olive trees and olive groves have been a favourite subject for some of the greatest artists. From the Renaissance painters of the 15th century to the contemporary painters, olives are depicted in various styles and forms, each a tribute to the magic of this tree.

Olive trees and olive groves have been a favourite subject for some of the greatest artists. From the Renaissance painters of the 15th century to the contemporary painters, olives are depicted in various styles and forms, each a tribute to the magic of this tree.

I remember, at one time during the early days of di Lusso, I collected fifteen prints of van Gogh’s olive paintings and hung them around the winery. The obsession faded, and the prints can’t be found. I’m sorry about that, but I can at least quote one of van Gogh’s many thoughts on the subject.

“The effect of daylight and the sky means there are endless subjects to be found in olive trees. For myself I look for the contrasting effects in the foliage, which changes with the tones of the sky. At times, when the tree bares its pale blossoms and big blue flies, emerald fruit beetles and cicadas in great numbers fly about, everything is immersed in pure blue. Then, as the bronzer foliage takes on more mature tones, the sky is radiant and streaked with green and orange, and then again, further into autumn, the leaves take on violet tones something of the colour of a ripe fig, and this violet effect manifests itself most fully with the contrast of the large, whitening sun within its pale halo of light lemon.”

Van Gogh is right, of course. The colours of an olive tree are extraordinary… at times khaki, at others almost emerald. Sometimes the tree is washed in grey.

And the fruit is similarly deceptive. Just when you think there’s nothing there, you can suddenly see a myriad of what look like peppercorns, well-camouflaged. These are the emerging olive flowers.

A week or so later – around mid-November – the canopy explodes in a white cloud of beautiful flowers. This is the time that we pray for windless days, to allow the fruit to set.

But in 2019, the same winds that drove the bush fire smoke towards Mudgee blew through our olive grove as well. And that was that! Flowers shriveled and burnt - practically no crop in 2020.

That’s farming!

But there are commercial risks on top of climatic ones. Most stem from mislabeling. Commercially, there are three different grades of olive oil made and marketed, around the world, from the high-quality extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) to medium-quality ordinary virgin olive oil, to low-quality olive-pomace oil (OPO).

EVOO is obtained by direct pressing or centrifugation of the olives. Its acidity can be no greater than 1 percent; if it is processed when the temperature of the olives is below 30°C - it is called cold-pressed. (Cold-pressing olives adds density of flavour and texture.)

Olive oils with between 1 and 3 percent acidity are known as "ordinary virgin" oils, but anything with greater than 3 percent acid and refined is " by accepted chemical solvents”, can also be fairly marketed as "ordinary." The dry or pulpy residue of the olive pressing process is called pomace, from which a liquid (such as juice or oil) has been pressed or extracted.

In Australia, all the supermarket chains seem to turn a blind eye to the mislabeling of ordinary virgin olive oil – in terms of country of origin (for example it is said that many Spanish olive oils are marketed as Italian) and many oils with more than 3% of acid are marketed as EVOO. But perhaps the most common adulterants in mis-labelled virgin olive oils are refined olive oil containing synthetic oil-glycerol products, seed oils (such as sunflower, soy, maize, and grapeseed), and nut oils (such as peanut or hazelnut).

So, if you’re interested in tasting the best, refer to a source such as Choice to decide which supermarket oils are ‘honest’ and put the list in your pocket when going shopping!

Rob

White Gold. The White Truffles of Alba.

Readers of this blog may have experienced – and hopefully enjoyed – a dish or two at a di Lusso Estate Truffle Day. We can only serve the black Perigord truffle – the only available type of truffle outside of the Alba region Piedmont in Italy, le Marche in central Italy and a small slice of the Balkans where the famed white truffle is found – and the experience is pleasant enough, but I must say not a patch on the white truffle that Luanne and I have experienced several times in Alba.

< Truffle country in Piedmont

Ignoring the peasants who associate the truffle with ‘just like toe jam’ (as we called the smell of our locker room youth), and those who claim the smell is that of testosterone (lucky analysts, I guess) the white truffle aroma, produced by soil bacteria trapped inside truffle-fruiting bodies, is best described as intensely musky, with a buttery, garlicky, sweaty intensity.

But the white truffle’s ability to transform the taste of a simple poached egg, bowl of linguini or even just a piece of toast, is extraordinary.

At our usual Barbaresco hotel – the Locanda Rabaya – shaved white truffle is served every evening for four weeks in late September/ October– almost always with pasta washed down with Barbaresco wine from the village itself. Unforgettable!

Recently, we saw the much- heralded Italian documentary Truffle Hunters, which traces the last few years of a community of old hunters and their dogs. There was no commentary; just the real-life conversations between hunters, between these old men and their dogs, interspersed with shots of the very lucrative global food industry that has been built around the white truffle. Poignant and beautifully filmed…. But sad, very sad.

These octogenarians could just not understand how what was happening….what was once a pastime enjoyed by Piemontese in the rugged hills of our favourite part of Italy had changed so dramatically. (We recognised many of the scenes in the documentary from walks we had enjoyed along the banks of the Tanaro, which flows around the town of Barbaresco).

Nowadays, conversations were more likely to be about truffle dogs being poisoned by jealous and unscrupulous competitors, families being separated by greed, men being unable or unwilling to retire even at the age of ninety as they chase the ‘next and final giant truffle’, ways to unfairly manipulate the price of white truffle price in the market headquarters in Alba by subterfuge.

A scene from the documentary….an elderly hunter enjoying dinner with his best friend.

And then I came across an article purporting to ‘capture the commercial essence of the white truffle industry'. It came complete with industry projections of market size (generally smaller each year), forecast downstream demand, SWOT analyses, CAGR market growth estimates, scenario after scenario etc etc etc. I couldn’t help thinking it was a pity that our ‘global economy’ had devalued yet another noble and ancient craft.

PS. The price of white truffles is quite astounding…the bigger the truffle, the higher the price by weight. In a ‘normal’ market, a very large white truffle will sell for well over $10,000 a kilogram.

In 2010, a white truffle weighing less than two kilos sold for US330,000! Needless to say, scientists around the world – led by the French, of course – are trying to grow the white truffle in other parts of our planet. Without success, so far at least!

Our Nebbiolo has origins in the Piedmonte region and is an excellent match for Truffles, or indeed any Italian meal that features mushrooms (Porchini Fungi Risotto, anyone?).

Robert

Vintage Reflections

Hi Everyone,

End of the vintage leads one to reflect on the wine of the current and previous seasons. Thinking about winemaking, here’s a little secret …. the best wines make themselves. Yes… that’s right… an excellent wine is one where a winemaker does just the “standard winemaking,” and the result is fantastic. “Great vintages begin in the vineyard”, it’s excellent fruit that makes winemaking easy.

For example, the 2018 vintage was very easy… A long summer, followed by a warm, dry autumn resulted in excellent fruit across the vineyard. And if you’re a lover of Mudgee wines, you’ll be happy to know that the whole region experienced above average levels of quality… but at the cost of a significant drop in yield (which is generally a good thing!). Our favourites wines that year were the Lagrein and the Arneis 2019 was undoubtedly a season of drought, with a dry summer following a dry winter. We took advantage of our very good irrigation setup to replicate a ‘normal’ European winter with weekly waterings through winter, so that during the hot summer the vineyard’s resistance to drought both below ground and in the canopy was higher. Like its predecessor, the 2019 outcome was high fruit quality but with a bigger crop.

For example, the 2018 vintage was very easy… A long summer, followed by a warm, dry autumn resulted in excellent fruit across the vineyard. And if you’re a lover of Mudgee wines, you’ll be happy to know that the whole region experienced above average levels of quality… but at the cost of a significant drop in yield (which is generally a good thing!). Our favourites wines that year were the Lagrein and the Arneis 2019 was undoubtedly a season of drought, with a dry summer following a dry winter. We took advantage of our very good irrigation setup to replicate a ‘normal’ European winter with weekly waterings through winter, so that during the hot summer the vineyard’s resistance to drought both below ground and in the canopy was higher. Like its predecessor, the 2019 outcome was high fruit quality but with a bigger crop.

Of the 2019 wines, at this stage (bearing in mind not all have been bottled), I particularly like the Sangiovese and the Barbera (including our first ever sparkling Barbera which we call Vivace! The 2019 Nebbiolo sits closely behind. Then along came the 2020 vintage. Were we tested? Yes! Firstly, the third year of drought brought a quite small and inconsistent – and late – flowering and fruit set. So late was fruit-set that the fires that began seriously in September and which brought a pall of smoke that hung over New South Wales for some months from October caused few problems for us. (But the same could not be said for many other growers, particularly those to the east of the town; or for unirrigated organic growers, whose fruit tends to flower earlier). Despite more sampling and tasting than ever before, we could find no fault in either the Arneis or the Vermentino were excellent. Then, a few weeks later, our early-picked Sangiovese (for Vino Rosato) checked out really well.

The 2020 reds required very careful handling. We were very away of the risks attached to ‘standard’ practices of ours. Maceration (that is, the soaking of skins during and after fermentation), oak maturation (we initially only used stainless steel for malolactic fermentation), and very frequent panel-tasting of the red wines before bottling. (None have been bottled yet). So far so good! We’ve not detected any smoke-taint so far in any of our own wines, but continue to be watchful. So, what’s my favourite wine from 2020? At this early stage, I would say the Vino Rosato, followed by Vermentino and Arneis. I’ll reserve my judgement on the reds until just before bottling, but my hopes are high.

Finally, talking about bottling. I aim to have our 2020 Vino Rosato released in June (“due to popular demand”), with the 2020 Vivo! sparkling next – in August. And remember, if you have any questions about the wines, please call or email me. I always look forward to a conversation with wine club members.

Regards

Rob Fairall

Ten Things to Consider when Cooking Italian

- Use ingredients that prioritise flavour, ahead of texture or aroma - which is quite different to the way of most French cooking

- Use precisely the right pan for each dish. Learn what’s ‘best practice’. The shape, size and thickness and compostion of each is critical to cooking outcomes.

- Well, a risotto should be made heavy-bottomed cast-iron skillet to get the soft gluey quality of a good risotto.

- A sauté pan, because of its depth and curved sides, is better for braising meat or vegetables than a frying pan.

- Pasta should be cooked in a cylindrical pot so the water returns to the boil more quickly once you have added the pasta, preventing the shapes from sticking together.

- Ragu, stews and pulses are cooked in pots made of earthenware, the best material for slow cooking, because it distributes the heat evenly.

- Season during cooking, not after. This rule is closely related to the rule below

- Use herbs and spices subtly, to enhance the flavour of the main ingredient, not to overwhelm it!

- A great battuto (a mixture of finely chopped vegetables) is vital. Look at cooking as a project on each occasion, and one worthy of following the advice of Aristotle (the world’s first professional project manager, “well begun, is half done”

- Keep an eye on your soffritto (a cooked battuto)… it cannot be allowed to burn!

- Use precise portioning of pasta to each sauce. It’s not hit and miss. Follow the recipe!

- Taste constantly while you cook. This rule is made easier to follow, as Italian food is mostly cooked on the stove and not in the oven.

- Serve pasta and risotto alone – don’t serve it with a with salad, side vegetables, meat or fish. Avoid the temptation to smother these two dishes with distractions

- Don’t overdo the parmesan, and never serve it with fish or seafood

Seasonal Diversity in Wine

My thoughts turned towards this topic earlier this week when receiving some cellar door feedback on our 2017 vintage wines. “A bit weaker than last years”, or “not as much flavour in this one, is there?”

How does one answer this sort of question to a non-farmer…the notion of seasonal diversity?. Particularly in today’s food big city world, when the last thing seemingly allowed is a flavour, texture or colour that is different from the last one?

Two things happen when it rains a lot around vintage. Firstly, there is disease. Downy mildew for sure, but also botrytis (not the nice kind), slip-skin, bunch rot etc. I wish grapes (and olives) could learn from figs in being so disease-resistant!

As the ‘usual’ date for picking draws near, you just know that the flavour and sugar are just not going to ‘get there’ before the canopy collapses. At this point, if you have enough wine in the cellar door, you just leave it on the vines – for the birds.

But we’re nearly always short of enough wine – certainly in 2017 – so the choice before us is between use every trick in the book – different yeasts, reverse osmosis (an expensive method of reducing volatile acidity, adjusting the level of alcohol, concentrating remove sulphides, etc). So the wine tastes just like the vintage before!

…or to do what we do. Enjoy the diversity and unpredictability of the world’s greatest beverage. In fact, it’s more than a beverage…it's a way of life!

Maybe I’m most of the way to being a ‘natural wine producer’? OK, so let’s see what makes them tick?

They would say honesty and transparency are the cornerstones of their craft. For a start, assume minimal chemical use. Maybe a splash of SO2 in the picking bin, that’s all in the vineyard – almost all natural winemakers are also organic, and also often micro-dynamic as well.

No introduced or inoculated yeast is used in natural winemaking– it’s “wild” but and natural, whereas inoculated yeast is still natural in a chemical sense.

The use of wild yeast is another topic altogether. ‘Extreme terrorism’, a common feature among natural winemakers, insists on it as these yeast by definition ‘wild’ (coming from the grapes, the vineyard – ‘from this place’, the definition of terroir.

The di Lusso Estate house view is that there are enough dangers and enough variety in winemaking without risking the disease, uncertain outcomes, and stuck ferments that come with come from wild yeasts!

Vermentino....a much travelled variety

A lot of Italian varieties share the same fate when it comes to missing their historical origins. Vermentino is like that. Although most suggest that the grape came from Gallura and spread in a circular motion in the middle ages, to me its highly unlikely this beautiful, uncomplicated wine would have begun its life in a little region in Sardinia,(its current ‘home base’).

Not romantic enough! There are other theories. The one that appeals to me most goes along the lines that Vermentino started its journey as a commercial wine in mainland Greece, as long ago as 2000 BC. (With this Greek heritage, it’s quite possible that its journey began even further back in time, to the Caucasus near Georgia and Armenia back in 4500 BC!).

This was when the first references were made to wine as a ‘social lubricant’. Nice term! Continuing the Greek theme, we note that in ancient times they founded over four hundred colonies in the Hellenistic period alone; including in Puglia, Sardinia, Basilicata and Sicily. The Greeks were well known for taking their favourite tipple with them, and so it was that Vermentino vines came to be planted in Italy.

The wine itself became particularly popular in the southern regions, which was where the Roman army tended to source their invasion kits – grains, vegetable seeds, grazing animals, etc – and vines for planting in their new environment). During the growth phase of the Roman Empire (around 100 to 20 BC), when France and Spain were settled, I’m guessing that’s when Vermentino went ‘offshore’. (In southern France in Provence and in the Languedoc-Roussillon where it’s still there, in the varietal name Rolle).

During the Dark Ages, Vermentino (and many other varieties) disappeared; but turn the clock forward thirteen hundred years or so, and the Spanish Hapsburgs reconquered Sicily (around 1500) - bringing back with them good old Vermentino. Spanish influence hung around Sicily, Sardinia and the southern mainland of Italy for over two hundred and fifty years in gentle sort of way, and Vermentino again thrived – mostly in Sardinia, Tuscany and Liguria.

As Europe headed towards the Napoleonic Age, Austria and France (of course Napoleon was more Italian than French in ancestry, spirit and even influence) replaced Spain in terms of influence down south and in the islands – and it seems they left without taking their Vermentino with them! In the last two hundred years or so, the variety has quietly emigrated from its two Italian regions – Sardinia/Tuscany with its more concentrated, sometimes oaked style, and Liguria, where it’s texture and body is very similar to Pinot Grigio –only the nose is different – chiefly to Australia United States.

Despite at times reading otherwise, I can say that di Lusso Estate produced the first commercial Vermentino; vintage 2003, from fruit grown by Bruce Chalmers in Euston (near Mildura).

Sangiovese......A grape with an 'interesting' history

Sangiovese is almost certainly the most popular Italian red variety in Australia - and in our di Lusso Estate portfolio. But it's not without a skeleton or two in the closet, and an interesting history. Read on!

Sangiovese is almost certainly the most popular Italian red variety in Australia - and in our di Lusso Estate portfolio. But it's not without a skeleton or two in the closet, and an interesting history. Read on!Navigating your way around the Sangiovese-Brunello-Montepulciano-Supertuscan Thing!

Working in the cellar door on any given Saturday, I’ll meet visitors who’ve been to Tuscany, or who worship Brunello, or who don’t know where Chianti fits into the landscape, or who think they know what a SuperTuscan is, or who think that Sangiovese is the grape from which the wine style Montepulciano Abbruzzo is made…and so on. Here how Italy’s most-grown grape hangs together – in the vineyard and in the bottle Sangiovese …the most important thing to remember about the grape variety Sangiovese has really only recently been definitively identified. (Previously, ‘Sangiovese’ was so commonly blended in both the vineyard and winery with other varieties – mostly with poor results- that its charm was not evident).

What has got the variety into ‘trouble’ at several levels is the fact that biologically the variety’s viticultural characteristics can vary enormously due to its sensitivity to location as to appear to be different varieties rather than just variants due to location (very similar to Pinot Noir in this respect). Over the past thirty years or so, many of the best producers have deliberately grown a range of different selections in their vineyards and this attention to detail has resulted in a massive improvement in overall quality. Brunello di Montalcino Nobody has done this more effectively than the good folk of this cute mountain village.

Although 100% Sangiovese, by a combination of careful clone and site selection, then longer maceration (fruit soaking to deepen the colour and extract tannins), the legal addition of 6% of concentrated must, and longer aging in both small oak barrels and in bottle before release, the region’s best wines taste quite different – deeper, richer, more opulent- than most of their fellow Tuscan styles. (One either believes in conspiracies or one doesn’t! For a number of years in the early part of this century the colour , concentration and fruitier flavours of Brunello were raising eyebrows. And true enough, in a scandal they called Brunello-gate, almost the whole Montalcino wine community; and in particular massive brands like Antinori and Frescobaldi, were found to be guilty of blending large amounts of ‘southern fruit’ with richer, darker characteristics that was illegal).

Overrated in my opinion; the sooner it becomes a wine more like the Chianti Classico Riserva, the better (see below!) Chianti and Chianti Classico Chianti is a region in central Tuscany. Nestled within it, between Florence and Siena, is the famous wine area known as Chianti Classico (declared by the Grand Duke of Tuscany as Italy's first legally protected wine region 301 years ago). Look for the Gallo Nero symbol, a black rooster inside a purple ring, on every bottle of Chianti Classico. These wines need only 80% Sangiovese to classify – although as the quality of the Sangiovese clones improve there is a growing number of 90 to 100% Classico wines.

There are three quality levels of Classico, depending on vineyard characteristics, age in barrel and time in bottle before release. SuperTuscan Wines In the 1970’s, the Italian government decided to do something serious to improve the quality of the country’s wines – and Tuscany’s in particular. So it undertook a massive audit of practically every vineyard in the country, discovering in the process that practically every vineyard contained an ‘assortment’ of varieties that did nothing to improve the quality of the wine. For example, most Tuscan vineyards contained a white variety Trebbiano and Canaiolo, a very mediocre red.

To bring a semblance of order to the industry, the authorities established an appellation system along the lines of that established in France, and urged all producers to work towards compliance. In parts of Tuscany, however, several leading winemakers had been experimenting with French varieties – in particular the Bordeaux varieties Cabernet Sauvignon and Franc, and Merlot, and they were very loathe to comply with the new ruling. Over a decade or so, they migrated many of their vineyards to an area around the village of Bolgheri,in western Tuscany where they produced wines that were smart enough to attract the attention of Robert Parker, at that time the leading wine advocate in the world.

Parker (who was renowned for goading the established wine order) is said to have exclaimed – after presumably awarding a whole bunch oh high ninety scores above those awarded to Bordeaux competitors that “These wines are not just Tuscan – they are SuperTuscan”. After that the marketing departments of the region over, the prices reputedly doubled, and a new wine ‘renegade style’ was born. An appellation not recognised by the authorities – to this day they carry an IGT (meaning, in a sense, Not Elsewhere Included), but created a new Italian wine style, one that is very sought!

Chill Your Reds?... Absolutely.

We are often asked whether one should chill a red before serving, and the answer is generally yes, and here’s why:

Alcohol has a boiling point of 78 degrees, which is significantly less than water. Therefore, the higher a wine’s temperature, the more enhanced the alcohol volatility, resulting in an “alcohol burn.”

This alcohol burn is first noticed when assessing the aromatics, and depending on the temperature, it can completely overpower a wine’s bouquet.

On the palate, the alcohol cuts through the fruit and accentuates the perceived dryness, resulting in a wine that tastes “hollow, hot and dry.”

People generally prefer not to drink red wine in summer, yet if they chilled the wine down to 16-22 degrees before serving, they would find that red wine goes down perfectly well, even on the hottest of summer days.

Yet how cold can you chill a red wine?

Chilling a wine, white or red, will enhance the wine’s perceived dryness, bitterness or astringency.

Phenolic compounds called tannins are what cause this “dryness,” and they are in a much higher level of concentration in reds than whites – which is why whites can be served ice cold, whereas reds generally cannot be served less than 12 degrees.

That is unless the red wine has a low level of tannin. And if you have been to di Lusso during summer, you may have noticed that we serve our Sangiovese Rosso and our Barbera in ice buckets.

As a rule of thumb, you should serve your reds between 16-22 degrees. This would mean putting the bottle in the fridge for 10 minutes or so before serving.

And if you know that the wine has a low level of tannin, and perhaps even a small residual sugar, the wine can be chilled as low as you’d like.

So, if it’s summertime and you’re not a fan of whites, choose a light red that can be chilled, and you’ll be pleasantly surprised at how well a chilled red wine can complement a meal, or be enjoyed on its own on the hottest of Australian summer days.

Machine Harvesting Olives - Video

2015 Harvest

A Sicma machine harvester at work...